Principal Director

Energy & Infrastructure | Projects, Infrastructure & Construction | Real Estate

This website will offer limited functionality in this browser. We only support the recent versions of major browsers like Chrome, Firefox, Safari, and Edge.

To celebrate the publication by the Joint Contracts Tribunal of the newest member of its family of standard form construction contracts – the JCT Target Cost Contract 2024 – we have produced two briefing notes on "target cost" contracting in the context of the UK construction industry.

This first briefing note discusses what target cost contracts are and how they work generally.

The second briefing note focuses specifically on the publication (and structure) of the JCT Target Cost Contract 2024 itself and can be found here.

Target cost contracts are a form of cost reimbursable contract, with the starting point being that a contractor is paid on an actual cost plus fee basis.

Here:

Importantly, no overall fixed cost for the works is agreed upfront, which is the case in many (if not all) standard forms of construction contract.

Instead, the parties agree an estimate of what they believe the works will cost – this being what is known as the "target cost". This should reflect a genuine and properly substantiated estimate of the likely cost of the works and should be developed between the parties on an open book basis. Getting the target cost as accurate/realistic as possible is critically important, as it will:

The parties also agree upfront what sums will not be payable to the contractor, commonly referred to as "disallowed costs" (e.g. costs not directly related to the works or that cannot be substantiated as having been incurred, etc.). What constitutes disallowed cost differs from contract to contract and is typically the subject of commercial negotiation. There is no "one size fits all" approach to it.

The contractor's accounts and records are regularly reviewed and assessed during the construction phase and up to the final account stage to ensure that any actual cost applied for has been properly incurred (and is not, as such, disallowed cost).

Following completion of the works, the "final cost" for completing everything (i.e. all actual cost plus the fee) is assessed against the target cost to determine whether the final cost of the works is lower than or higher than the target cost, which will result in either an underspend (saving) or an overspend against the target cost (i.e. the estimate turned out to be higher or lower than what the works actually cost).

How the final cost is defined differs between contracts, but the principle is broadly the same in each.

(In this briefing note, it is assumed that the "target cost" includes the fee on the anticipated actual cost, but this is not always the case. Care should be taken to ensure that this is made clear at the outset to avoid any confusion and potential disputes over any "pain" and "gain", as discussed below.)

Under a target cost model, any:

against the target cost for the works is shared between the parties in pre-agreed proportions. This is generally known as the "pain/gain share".

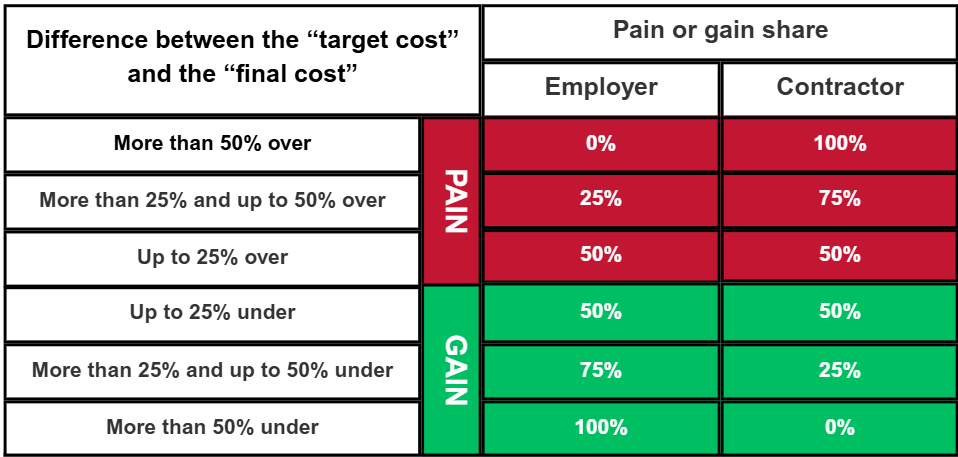

The table below sets out a basic example of how a pain / gain share split might look in practice, assuming that each party's share will move up or down depending on the level of the underspend/overspend:

In this example, if the original target cost for the works was £10,000,000 but the final cost is £16,000,000 (i.e. 60% over):

Conversely, if the cost of the works comes under budget, the contractor would be entitled to additional payment to reflect any actual cost not spent (almost like a bonus), this being its share of the underspend (the "gain") on a similar basis. For example, if the final cost of the works was £9,000,000 (i.e. 10% under target cost), the £1,000,000 saving would be shared between the parties 50:50 (so, £500,000 each).

Some contracts assess pain / gain on a continual basis throughout the delivery of the project (i.e. as part of interim payments) and others solely at the end of the project. The mechanism just depends on what the parties agree at the outset.

(Due to the nature of target cost contracts and the fact that the original target cost is based on an estimate, it is possible, if slightly improbable, that the final cost of the works will be exactly equal to the original target cost, in which case there is no gain or pain to deal with.)

Importantly, the "day one" target cost is typically adjusted during the construction of the works to account for things like variations and delay events, much like a fixed cost would be adjusted under other forms of contract.

This ensures that:

The events which trigger adjustments to the target cost differ from contract to contract (e.g. NEC contracts use "compensation events", JCT contracts use "Relevant Matters" etc.) and are generally, again, subject to negotiation to take into account any project-specific issues and agreed risk sharing.

Target cost contracts encourage parties to work together to proactively (and openly) manage the costs and risks associated with delivering works.

In fixed cost contracts, contractors include risk allowances in their fixed prices to limit their exposure to unrecoverable costs should certain events occur (e.g. delays). Here, the employer pays the risk allowances irrespective of whether the events priced for actually occur or not (e.g. a potential need to remediate contaminated land).

Target cost contracts encourage such risk allowances to be factored into the target cost at the outset, to limit a contractor's exposure to "pain" in the event of an overspend against the target cost, but the contractor will only be paid what it has incurred in carrying out and completing the works (as actual cost).

So, if a risk that has been factored into the target cost does not occur, the employer does not (in theory) pay the contractor the allowance (noting that "gain" might be payable where the final cost comes under the target cost). This makes agreeing the "day one" target cost an art in itself, which is a story for another day.

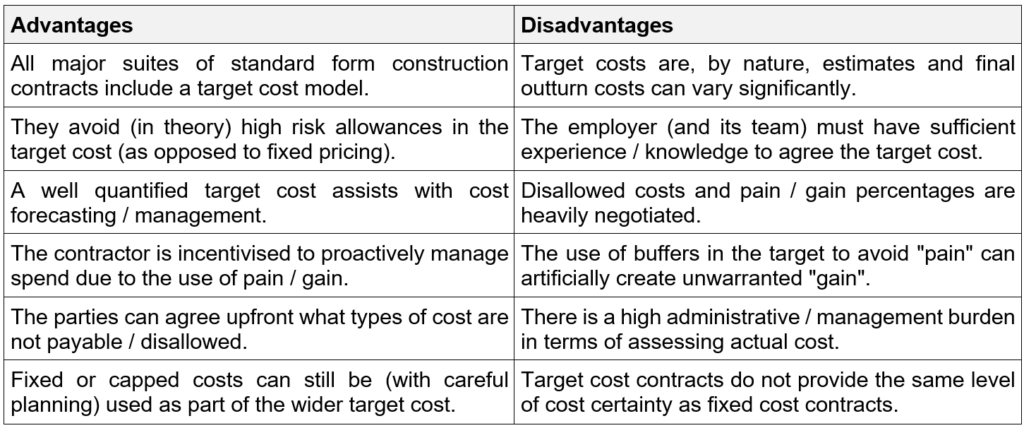

As with any contract model, target cost contracts have both advantages and disadvantages:

Target cost contracts are commonly used on major infrastructure projects in the UK and beyond. With the publication of the JCT Target Cost Contract 2024, target cost contracts are likely to become increasingly common across all sectors. This will be especially so in a climate where securing value for money and balancing not just the books, but also risk allocation, is critically important to the success of projects.

Whilst they can look and feel very much like "traditional" construction contracts, care should always be taken to ensure that all parties and their professional advisers fully understand the structure of (and any form-specific idiosyncrasies in) any target cost contract that they use, as well as recognise the level of day-to-day involvement (particularly from a contract administration perspective) and collaboration that is required to ensure that a project is delivered successfully.

Please get in touch if you would like to speak to one of our sector experts about the ins and outs of target cost contracting and the pros and cons of using the contracts on your projects, as well as on anything construction and infrastructure-related generally.